Feedforward neural network

A feedforward neural network is an artificial neural network where connections between the units do not form a directed cycle. This is different from recurrent neural networks.

The feedforward neural network was the first and arguably simplest type of artificial neural network devised. In this network, the information moves in only one direction, forward, from the input nodes, through the hidden nodes (if any) and to the output nodes. There are no cycles or loops in the network.

Contents |

Single-layer perceptron

The earliest kind of neural network is a single-layer perceptron network, which consists of a single layer of output nodes; the inputs are fed directly to the outputs via a series of weights. In this way it can be considered the simplest kind of feed-forward network. The sum of the products of the weights and the inputs is calculated in each node, and if the value is above some threshold (typically 0) the neuron fires and takes the activated value (typically 1); otherwise it takes the deactivated value (typically -1). Neurons with this kind of activation function are also called Artificial neurons or linear threshold units. In the literature the term perceptron often refers to networks consisting of just one of these units. A similar neuron was described by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in the 1940s.

A perceptron can be created using any values for the activated and deactivated states as long as the threshold value lies between the two. Most perceptrons have outputs of 1 or -1 with a threshold of 0 and there is some evidence that such networks can be trained more quickly than networks created from nodes with different activation and deactivation values.

Perceptrons can be trained by a simple learning algorithm that is usually called the delta rule. It calculates the errors between calculated output and sample output data, and uses this to create an adjustment to the weights, thus implementing a form of gradient descent.

Single-unit perceptrons are only capable of learning linearly separable patterns; in 1969 in a famous monograph entitled Perceptrons Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert showed that it was impossible for a single-layer perceptron network to learn an XOR function. It is often believed that they also conjectured (incorrectly) that a similar result would hold for a multi-layer perceptron network. However, this is not true, as both Minsky and Papert already knew that multi-layer perceptrons were capable of producing an XOR Function. (See the page on Perceptrons for more information.)

Although a single threshold unit is quite limited in its computational power, it has been shown that networks of parallel threshold units can approximate any continuous function from a compact interval of the real numbers into the interval [-1,1]. This very recent result can be found in [ Peter Auer, Harald Burgsteiner and Wolfgang Maass: A learning rule for very simple universal approximators consisting of a single layer of perceptrons, 2008].

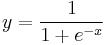

A multi-layer neural network can compute a continuous output instead of a step function. A common choice is the so-called logistic function:

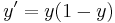

(In general form, f(X) is in place of x, where f(X) is an analytic function in set of x's.) With this choice, the single-layer network is identical to the logistic regression model, widely used in statistical modeling. The logistic function is also known as the sigmoid function. It has a continuous derivative, which allows it to be used in backpropagation. This function is also preferred because its derivative is easily calculated:

(times

(times  , in general form, according to the Chain Rule)

, in general form, according to the Chain Rule)

Multi-layer perceptron

This class of networks consists of multiple layers of computational units, usually interconnected in a feed-forward way. Each neuron in one layer has directed connections to the neurons of the subsequent layer. In many applications the units of these networks apply a sigmoid function as an activation function.

The universal approximation theorem for neural networks states that every continuous function that maps intervals of real numbers to some output interval of real numbers can be approximated arbitrarily closely by a multi-layer perceptron with just one hidden layer. This result holds only for restricted classes of activation functions, e.g. for the sigmoidal functions.

Multi-layer networks use a variety of learning techniques, the most popular being back-propagation. Here, the output values are compared with the correct answer to compute the value of some predefined error-function. By various techniques, the error is then fed back through the network. Using this information, the algorithm adjusts the weights of each connection in order to reduce the value of the error function by some small amount. After repeating this process for a sufficiently large number of training cycles, the network will usually converge to some state where the error of the calculations is small. In this case, one would say that the network has learned a certain target function. To adjust weights properly, one applies a general method for non-linear optimization that is called gradient descent. For this, the derivative of the error function with respect to the network weights is calculated, and the weights are then changed such that the error decreases (thus going downhill on the surface of the error function). For this reason, back-propagation can only be applied on networks with differentiable activation functions.

In general, the problem of teaching a network to perform well, even on samples that were not used as training samples, is a quite subtle issue that requires additional techniques. This is especially important for cases where only very limited numbers of training samples are available.[1] The danger is that the network overfits the training data and fails to capture the true statistical process generating the data. Computational learning theory is concerned with training classifiers on a limited amount of data. In the context of neural networks a simple heuristic, called early stopping, often ensures that the network will generalize well to examples not in the training set.

Other typical problems of the back-propagation algorithm are the speed of convergence and the possibility of ending up in a local minimum of the error function. Today there are practical solutions that make back-propagation in multi-layer perceptrons the solution of choice for many machine learning tasks.

ADALINE

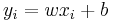

ADALINE stands for Adaptive Linear Element. It was developed by Professor Bernard Widrow and his graduate student Ted Hoff at Stanford University in 1960. It is based on the McCulloch-Pitts model and consists of a weight, a bias and a summation function.

Operation:

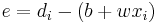

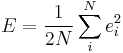

Its adaptation is defined through a cost function (error metric) of the residual  where

where  is the desired input. With the MSE error metric

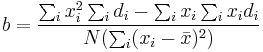

is the desired input. With the MSE error metric  the adapted weight and bias become:

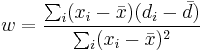

the adapted weight and bias become:  and

and

The Adaline has practical applications in the controls area. A single neuron with tap delayed inputs (the number of inputs is bounded by the lowest frequency present and the Nyquist rate) can be used to determine the higher order transfer function of a physical system via the bi-linear z-transform. This is done as the Adaline is, functionally, an adaptive FIR filter. Like the single-layer perceptron, ADALINE has a counterpart in statistical modelling, in this case least squares regression.

There is an extension of the Adaline, called the Multiple Adaline (MADALINE) that consists of two or more adalines serially connected.

See also

References

- ^ Roman M. Balabin, Ravilya Z. Safieva, and Ekaterina I. Lomakina (2007). "Comparison of linear and nonlinear calibration models based on near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy data for gasoline properties prediction". Chemometr Intell Lab 88 (2): 183–188. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2007.04.006.

- Auer, Peter; Harald Burgsteiner; Wolfgang Maass (2008). "A learning rule for very simple universal approximators consisting of a single layer of perceptrons". Neural Networks 21 (5): 786–795. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2007.12.036. PMID 18249524. http://www.igi.tugraz.at/harry/psfiles/biopdelta-07.pdf.